By (Image: courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine) – Pandemic Influenza: The Inside Story. Nicholls H, PLoS Biology Vol. 4/2/2006, e50 https://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040050, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1441889

- Governor Newsom announced the start of Phase II of California’s COVID-19 response today by allowing limited pick-up service openings for businesses like book stores, sporting goods stores, and florists as early as this coming Friday. This is a measured loosening of restrictions to be sure as there’s no real congregating allowed and this is probably the most that could safely be undertaken at this point. We have not met several of the criteria outlined by infectious disease experts for safe relaxation of stay-at-home orders. In particular, while testing is increasing, we are not at the level where comprehensive evaluation of any symptomatic person can be achieved with results on the same day or within hours. Additionally, it’s not clear that daily new cases are declining let alone for 14 days straight, another of the primary relaxation criteria. Given this, it’s a bit of a risk to begin loosening of restrictions at this point but I’m guessing he hopes allowing these relatively safe activities will help put an end to the incredibly risky behavior of protesters around the state in recent days. Some experts like Dr. Robert Kim-Farley from UCLA are predicting that Phase III which will include the opening of higher risk businesses like movie theaters and gyms might occur sometime in the late summer, possibly August or September. Timelines like this are notoriously difficult to predict however, since they sometimes depend on non-medical decision making by political leaders. I wouldn’t be shocked to see that timeline bumped up somewhat.

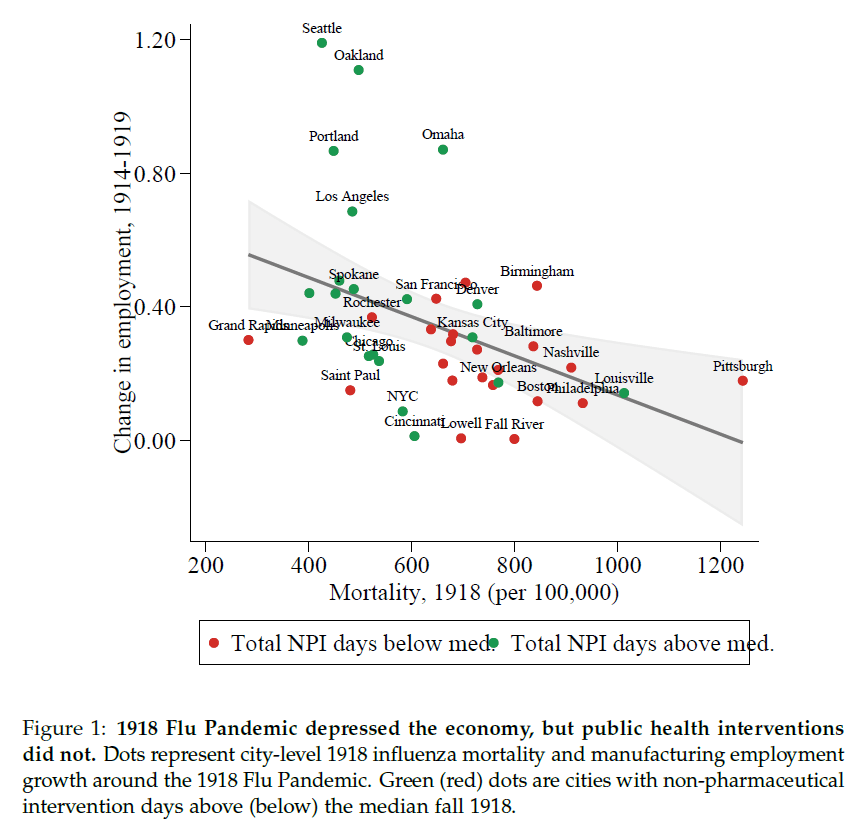

- It seems pretty clear now that the United States’ COVID-19 disease course is not following a Gaussian curve with an equal slope on the way up to and down from the peak. Instead the disease is declining at a much slower rate than when it ramped up to the peak. This slow tapering recovery will unfortunately lead to significantly more cases and deaths from the initial disease surge than predicted by models that assume a Gaussian distribution as there will ultimately be more area under the curve.

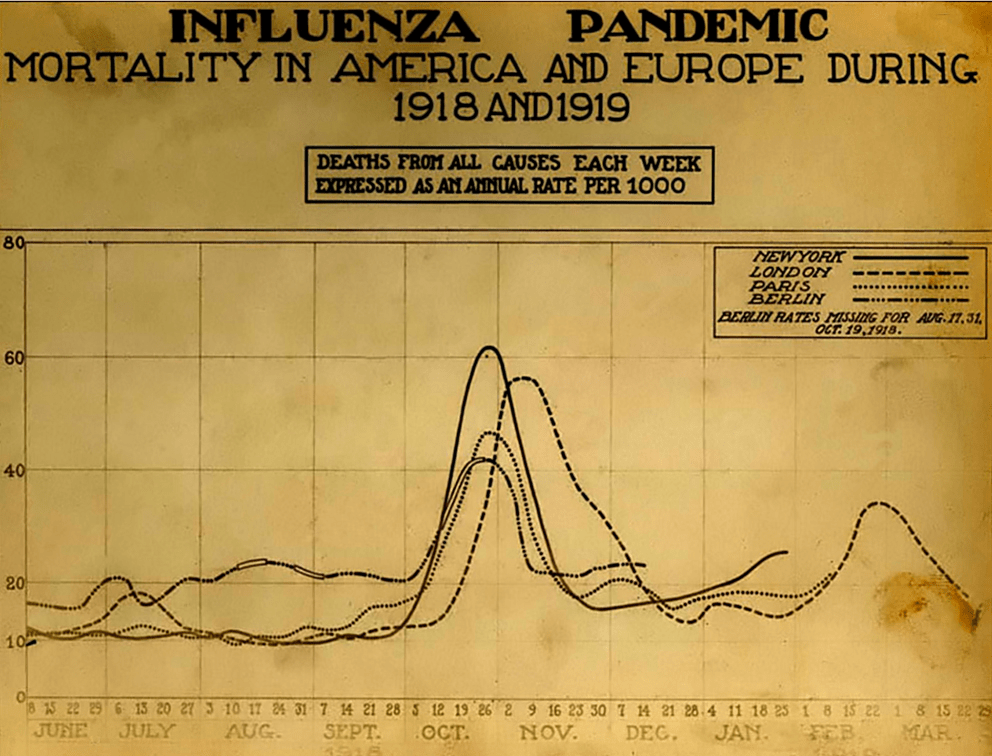

- Michael Osterholm, a foremost expert on viruses and pandemics who many people saw for the first time on Joe Rogan’s podcast is the Director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). Last week his group at CIDRAP released a report that describes three possible pandemic wave scenarios based on lessons learned from previous pandemics. The first scenario sees one to two years of recurring peaks and valleys similar to what we’ve just experienced requiring periodic reinstitution of mitigation measures like we’re currently living under. For obvious reasons, this scenario could have dramatic economic repercussions. The second scenario mimics the 1918 influenza pandemic which saw an initial peak in the spring and a massive, much more devastating peak in the fall after relaxation of social distancing measures during the summer. This second peak would almost certainly overwhelm our healthcare system and lead to very large numbers of deaths but would not be followed by significant peaks after the fall peak as the virus would have burned through most of the population. The third scenario describes a slow burn after the current, initial surge. In this scenario there are no peaks and valleys, just a constant relatively stable number of ongoing cases and deaths. This scenario would not require large-scale mitigation measures after the initial peak. While this pattern has not been seen with previous influenza pandemics it could occur with a novel coronavirus such as SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19. Whatever scenario plays out, the CIDRAP group advises that Americans should get used to the idea of significant COVID-19 activity for the next 18-24 months. As the pandemic starts to fade away, it’s likely that SARS-CoV-2 will continue to cause less and less severe illness over the next decade eventually settling in as a non-life threatening upper respiratory infection much like it’s other cold-causing coronavirus cousins.