:format(webp):no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19885359/1208432585.jpg.jpg)

Sweden’s approach to COVID-19 is different from most countries. Is it working there? Should the US have adopted this strategy? A closer look at the Swedish experience reveals significant problems with the Scandinavian country’s approach and highlights inherent differences between the two countries that largely prohibit its application in the US.

Facing a novel Coronavirus with a doubling time of around 2 days, most of the world reacted to SARS-CoV-2 with what can only be described as justifiably draconian measures to slow the spread. Absent mitigation and with a doubling time of 2 days, the US would have seen the virus hit every American within about 40 days. America, like most of the world, enacted emergent stay-at-home and social distancing orders and closed non-essential businesses to flatten the curve. Too many infections too quickly would have completely overwhelmed the healthcare system, tragically demonstrated in Wuhan and Lombardy where the virus had a devastating head-start.

Several prominent European countries undertook a different strategy. England, the Netherlands and Sweden instituted what is considered a herd-immunity approach. While it’s important to note that England and the Netherlands had to abandon this blueprint when cases and deaths started climbing, Sweden has largely stuck with the plan. The idea behind this is that in the absence of a vaccine, the only way to move on from a virus like this is to allow herd-immunity to develop. The purest form of this approach would be to just let the virus burn through a population and allow everyone to become infected, but at the cost of thousands of lives and an overwhelmed healthcare system. Sweden didn’t go that far but instead attempted to find a middle-ground. They executed a much less restrictive approach than other nations and allowed businesses, restaurants, bars, and gyms to to stay open while enacting certain social distancing rules for the owners and patrons to follow. The Swedish government, instead of stay-at-home orders, recommended that Swedes voluntarily enact social distancing by working from home and keeping an arm’s length distance when around others. It’s somewhat like a controlled burn approach with the goal of keeping the virus down to about 30% of its normal spread while focusing on the protection of vulnerable populations.

On the surface, Sweden’s approach seems to be working for them. Without enacting strict, often unpopular laws, Sweden has effectively flattened the curve and prevented a hospital crisis. The government believes that in Stockholm at least, a significant portion of the population has been infected and that they may be closing in on herd immunity but this is a projection without solid data confirmation as comprehensive serology testing has not yet been fully undertaken. Results in Sweden have led some here in the United States to suggest that Sweden is evidence that the response to COVID-19 has been an overreaction to a virus that is not as severe as experts would have us think and that Sweden’s strategy should have been adopted here to soften the economic blow.

Let’s take a look at the Swedish experience to see whether these claims have merit and whether they could have been successfully adopted in the US.

First I think it’s important to determine whether their approach is as different as it seems. While there’s no stay-at-home order in Sweden, there are public health orders in place to increase social distancing. High schools and colleges were closed, gatherings of over 50 people are prohibited, in restaurants and bars, patrons must maintain arm’s length distance from one another. Instead of orders, Sweden called on its citizens to voluntarily enact social distancing principles. The population was asked to work from home, avoid unnecessary travel and maintain distance from others. Swedes seem to have largely adopted these measures. Data suggests that movement in the streets of Stockholm was down to 30 percent of normal, a number that in many cases surpasses US reductions in movement even in the regions most compliant with mandated stay-at-home orders. Upwards of 50% of Swedes transitioned to working from home and use of public transit dropped in half as well. Even vacations have been canceled with 85% of Swedes reporting that they would not be taking the usual annual pilgrimage to the resort island of Gotland.

Whether mandated or not, a voluntary stay-at-home policy is still a stay-at-home measure. Swedish ideology is rooted in a deep respect for social justice. Heba Habib at the Christian Science Monitor who has followed the Swedish experience with COVID-19 reports that Swedes take great pride in their personal responsibility. The idea of breaking the social contract of social distancing by holding a mass gathering or flocking to the beach at the first sign of sun would be flatly rejected by Swedes.

Sweden promotes itself as being a model society based on values of social justice and human rationality, with a high level of trust between people and trustworthy authorities. This has its origins from the Social Democrat-introduced concept of “Folkhemmet,” or people’s home, where a welfare state cares for all with the proviso that everyone complies with a communal order.

Heba Habib/Christian Science Monitor

In effect, Swedes largely trust their authorities to do what’s best for the people with respect to COVID-19 and in return they have generally complied with voluntary COVID-19 orders when asked to do so by their government. The Swedish experience with COVID-19 has been reliant on this trust in government and the importance of maintaining the social contract. Though falling somewhat in recent years, the OECD index on government trust shows Swedes trust their government quite a bit more than Americans do. For the Swedish approach to work in the US, Americans would have to show the same willingness to take the governments assessment of virus severity and subsequent social-distancing recommendations as truth and follow them without legal mandate to do so. Americans suggesting that Sweden’s approach should be ours, must honestly answer if it is part of US national identity to trust and comply with government in this way.

So has the Swedish approach worked? If the only metric by which you measure success is flattening the curve to prevent overwhelming hospitals, then yes, Sweden has succeeded for now. It’s possible that Stockholm has peaked though data is not yet conclusive and it is too early to tell if the nation has peaked. Youyang Gu’s universally praised, highly predictive model estimates an overall infection rate of about 5% in Sweden; that is nowhere near numbers needed for herd immunity. It would seem there are still a lot of people left for the virus to burn through.

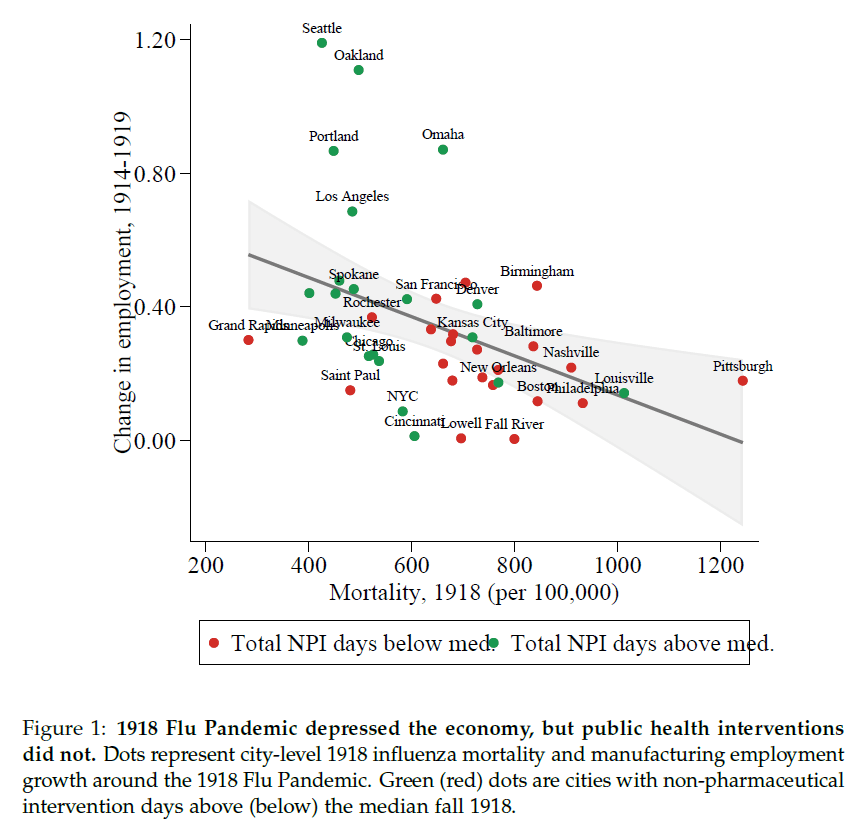

What about their deaths? Have they protected the people from dying, particularly the vulnerable? If this is the metric of success, then Sweden’s approach has not been particularly successful. Deaths in Sweden are proportionately higher than their Scandinavian neighbors who enacted stricter social distancing measures.

These deaths have hit vulnerable populations in Sweden hard. About 50% of all deaths in Sweden have occurred in elder care facilities. One of the goals of the Swedish approach was to protect these vulnerable populations; in that they have not been particularly successful. If your metric for measuring success is preventing death, particularly among the vulnerable, then Sweden has come up short.

One of the arguments made here in American by people opposed to the social distancing orders is the effect these measures have on the economy. They point to Sweden as an example of a country that has been able to keep its economy open in spite of COVID-19. If we take a closer look at their economy, however, Sweden is not fully escaping the toll this virus has taken on other nations with more aggressive lockdowns. The Swedish Finance Minister projected that the economy would shrink by 7% which was a worsening of previous projections. This contraction is similar to the projected contraction in the Netherlands and depending on how the virus behaves, could be as much as 10%. Unemployment is expected to reach 11%. That’s certainly better than the US’s expected 20-30% unemployment. It’s important to remember, however, that the Swedish government helps to prevent unemployment by giving employers money to keep people on payroll. To compensate for reduced employee hours and business productivity losses, employers are permitted to cut salaries but the government then supplements employee pay up to 90% of original salary. The US has attempted to pass legislation that similarly protects jobs by providing forgivable loans to businesses who keep people on the payroll. The roll-out has been fraught with problems and the money quickly dried up before most could benefit. Businesses have had to let people go while waiting for assistance, driving up unemployment rates. The US focus has been to provide one-time payments to most Americans and to bolster the unemployment benefits system. Sweden’s very different approach is of course paid for in part through a very different taxation strategy than in the US. The top statutory personal income tax rate in Sweden in 2018 was 57% and applies to all earners who are making 1.5 times the national average and in the US, the top rate of 43.7% applies only to people who make over 9 times the national average. I bring this up not to advocate for a Swedish welfare state or for the US to adopt the Swedish system of taxation. It is, however, important to consider the apples to oranges differences in Swedish and US economic strategies when suggesting that adopting the Swedish approach to COVID-19 would work in America or that we would see the same economic benefits.

There are other factors which make the Swedish experience somewhat unique and difficult to apply elswhere. Their population density is significantly lower and they have far less travel into the country than their harder hit neighbors in Europe. Inbound tourism is dwarfed by countries like Spain, Italy and France and the US. According to the World Tourism Organization, in 2017, Sweden had 7M inbound tourists compared with almost 77M inbound tourist to the US. With fewer people traveling into the country, Sweden was able to avoid massive importation of the virus making their initial contact tracing efforts exponentially easier to manage.

So this has all been a long-winded way of saying that Sweden’s approach is not the panacea some in the United States claim. In fact, 22 of Sweden’s top research and infectious disease scientists recently wrote an op-ed in a national newspaper calling on the government to enact strict social-distancing and stay-at-home orders matching other nations. They’re concerned about Sweden’s high number of deaths and continuing increases in new daily cases, especially in vulnerable populations. As they see it, Sweden is headed for a disastrous surge in cases which could soon overwhelm their healthcare system.

I can’t say that Sweden has been completely wrong-headed about their approach. It’s simply too early to tell. The world should study their model and learn from it to see if it ultimately demonstrates a benefit. A comprehensive review of all the factors that contribute to a nation’s success or failure in the fight against COVID-19 is far beyond the scope of this blog post and, frankly, beyond the knowledge of its author. My goal here is to simply point out that fundamental differences in our two countries make for difficult comparisons and tougher still, conclusions. The idea that the Swedish experience proves the public health response in the US was an overreaction to an overhyped virus is unsupported by the facts. It’s also folly to suggest that the Swedish model, not yet shown to be successful even in Sweden, would work in America. The differences between our two countries both physically and temperamentally are vast. Ignoring these fundamental differences and assuming that the Swedish approach to COVID-19 would be successful if adopted here is woefully naive even if politically expedient.

Time will tell if the Swedes have successfully ridden the wave of COVID-19 into herd immunity without the need for government orders, or if all they’ve done is push their peak down the road a bit and that dark days lie ahead for them.