“The cure can’t be worse than the disease.”

This is a common and somewhat understandable refrain in recent months. Is the damage to the economy caused by public health interventions like social distancing and shelter-in-place worse than the potential damage of COVID-19 itself? Is the cure worse than the disease? How can we know?

“The farther backward you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.”

Winston Churchill

History can help us if we’re willing to learn from it. Several economists have taken a bite out of this problem with very interesting results. Prof. Emil Verner from the MIT Sloan School of Management along with Dr. Sergio Correia and Dr. Stephan Luck from the Federal Reserve have done what more of us should do–learn from history. Together these economists studied social distancing practices or non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) from the Spanish Flu of 1918 to evaluate the effects of social distancing on the economy. Their paper is not yet peer-reviewed but it provides some compelling insights into the efficacy of public health interventions in a pandemic and the resulting economic impacts.

The 1918 influenza pandemic is thought to have infected nearly a third of the world’s population at the time or 500 million people. In the United States alone, 675,000 people died, worldwide–50 million. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Public health measures at the time were focused on prevention of spread from person to person. Those infected were prevented from breathing the same air as the uninfected. Public health guidelines and interventions at the time included prohibiting mass gatherings, banning non-essential meetings, closing dance halls, bars and cinemas, and some encouraged staggered work times to prevent unnecessary congregation. All pretty familiar stuff today, right? Like today, the degree to which these recommendations were followed varied widely throughout the country.

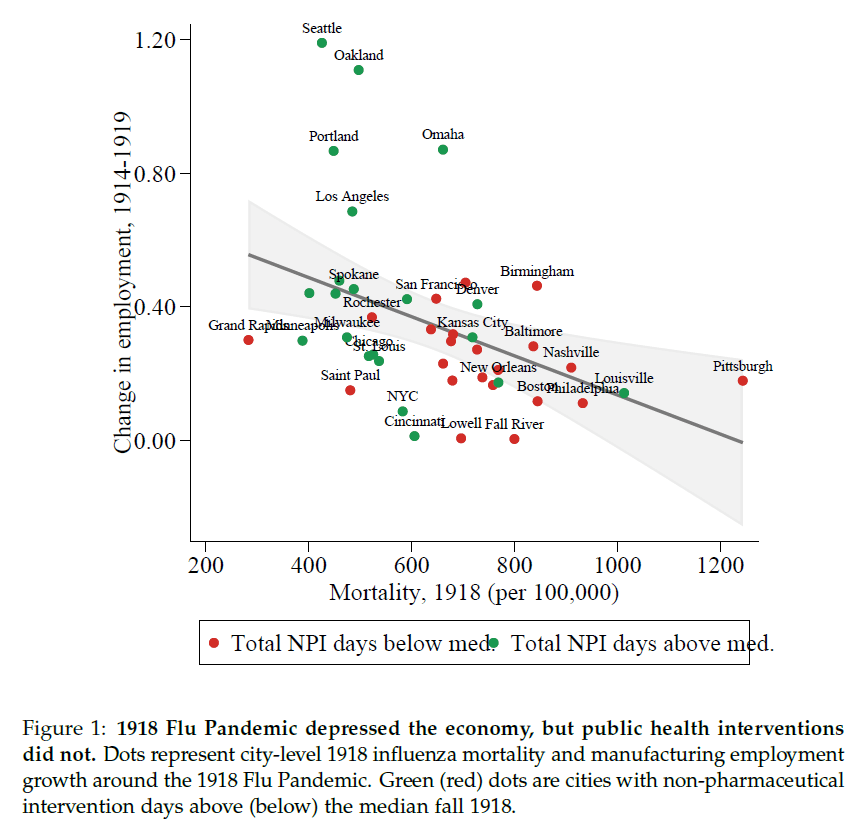

What Verner, Correia and Luck found was that, as expected, higher mortality in a region led to greater economic depression. More than that though, they looked at American Cities’ response and compared the economic impact of municipalities who enacted strict social distancing measures with those who enacted much weaker measures. Here they found that cities who enacted the strictest social distancing measures had lower mortality but they also experienced the greatest economic growth. Simply put, cities that were committed to public health measures like social distancing had fewer deaths and better economic outcomes.

The green-dot cities in the upper left who enacted strict NPIs like social distancing over longer periods had lower mortality and higher economic growth whereas the red-dot cities in the lower right, who were more lenient with NPIs, experienced higher mortality and stunted economic growth. The authors say it best.

Comparing cities by the speed and aggressiveness of NPIs, we find that early and forceful NPIs do not worsen the economic downturn. On the contrary, cities that intervened earlier and more aggressively experience a relative increase in manufacturing employment, manufacturing output, and bank assets in 1919, after the end of the pandemic.

Emil Verner, Dr. Sergio Correia and Dr. Stephan Luck/Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu

The economic impacts of this pandemic on families and businesses has been devastating. Public health measures like shelter-in-place and social distancing are a bitter pill to be sure. History tells us, however, that this medicine, while hard to swallow, gives us the best chance of surviving, both medically and economically.

Future generations will study this moment, perhaps as they face their own crisis. Just like us they’ll be looking for clues from the past about how to survive. Will they see ancestors rooted in solid science with an unwavering commitment to public health, or will they see a fleeing from science and reason when things got hard? I’m not sure.

In the end, history will judge.